Among the many apocalyptic writings preserved outside the canonical Bible, few are as haunting and profound as 2 Esdras (also known as 4 Ezra). But a natural question arises: Is this text authentic? And if so, in what sense?

To answer this, we must address two main issues:

-

When was 2 Esdras written?

-

Could Ezra the Scribe have authored it?

Let’s examine both with facts, not assumptions.

🕰️ Was 2 Esdras Written Around 90–100 AD?

✅ Most scholars date 2 Esdras (chapters 3–14) to 90–100 AD, based on:

-

Clear references to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD

“Our sanctuary is laid waste, our altar broken down” (10:21–22). -

The Eagle vision (chapters 11–12), which likely represents the Flavian dynasty of Roman emperors (Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian), who ruled from 69–96 AD.

-

Its absence from the Dead Sea Scrolls, which makes sense if it was written after the Qumran community was destroyed in 68 AD.

-

Its theological and literary similarities to 2 Baruch, another Jewish apocalypse also dated to the late 1st century.

🤔 Could That Date Be Wrong?

A few minor scholarly voices have suggested slightly earlier or later dates:

-

Some date it as early as 70–80 AD, interpreting the lamentation over the Temple as immediate.

-

Others argue for 100–120 AD, especially if 2 Baruch used 4 Ezra as a source.

-

But no credible scholar places it before 70 AD (the Temple was still standing) or after 135 AD (no mention of the Bar Kokhba revolt or Hadrianic persecution).

📌 Conclusion: The 90–100 AD window is not arbitrary — it’s grounded in historical context, internal clues, and comparative analysis.

🧔 Did Ezra the Scribe Write 2 Esdras?

This is where traditional views and historical facts part ways.

Traditional Claim:

-

In some Christian traditions (especially the Ethiopian Church), the book is accepted as scripture and attributed to Ezra, the famous priest and scribe from the 5th century BC.

Historical Reality:

-

The book of Ezra in the Bible is a historical narrative focused on temple restoration under Persian rule.

-

2 Esdras, by contrast, is an apocalyptic vision full of angelic dialogues, symbolic animals, and end-times judgment.

-

The language of 2 Esdras survives primarily in Latin, Syriac, and Ethiopic—not Hebrew or Aramaic, which Ezra would have used.

-

The text references Jerusalem and the Temple as already destroyed, something that occurred centuries after Ezra’s time.

-

The political power (the eagle) represents Rome, not Persia.

📌 Conclusion: Ezra did not write 2 Esdras. Like many ancient texts, it was written pseudonymously, using Ezra’s name to give it authority during a time of crisis.

🔥 Why Does This Matter?

If 2 Esdras was written after the Temple’s destruction, then:

-

It reflects the deep trauma and spiritual questions of a devastated Jewish people.

-

It becomes a bridge between Biblical prophecy and later Jewish-Christian apocalyptic literature (including the Book of Revelation).

-

Its visions of judgment, tribulation, and messianic hope make it especially relevant for those seeking to understand the spiritual meaning of suffering and the end of the age.

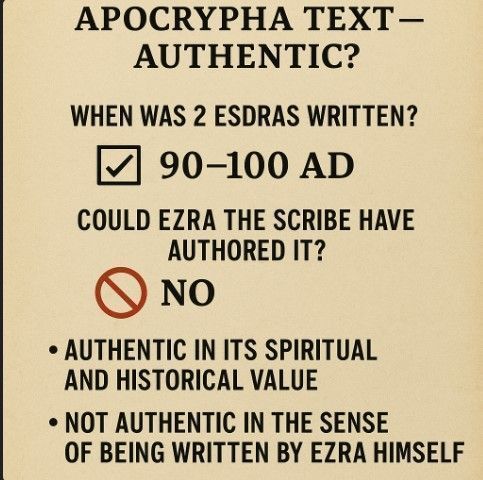

🧠 Final Verdict: Is It “Authentic”?

Yes — authentic in its spiritual and historical value.

No — not authentic in the sense of being written by Ezra himself.

2 Esdras is a genuine Jewish apocalypse, written by a faithful Israelite after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD. It speaks powerfully to themes of judgment, hope, and endurance — messages that resonate deeply with those preparing for tribulation in our time.

🧑🏫 Who Most Likely Wrote 2 Esdras (4 Ezra)?

❌ Not Ezra the Scribe (Historical Figure)

-

Ezra lived in the 5th century BC, during the Persian period.

-

2 Esdras describes Jerusalem as already destroyed, matching 70 AD, not Ezra’s time.

-

Literary form is apocalyptic, unlike the narrative and priestly concerns of the Biblical Ezra.

-

Language evidence: The original may have been in Hebrew or Aramaic, but all surviving versions are late translations (Latin, Syriac, Ethiopic)—no Hebrew copy has ever been found.

Conclusion: Ezra’s name is used as a literary device, not as actual authorship.

✅ Most Likely: A Post-70 AD Jewish Apocalyptic Author

Clues to His Identity:

-

Anonymous: The author never names himself in the first person.

-

Deeply learned in Jewish Scripture: The text weaves references from the Torah, Psalms, Prophets, and wisdom literature.

-

Mourning the Temple's Destruction: The tone shows personal anguish over the fall of Jerusalem.

-

Uses coded imagery (e.g., “Babylon” = Rome; “Eagle” = Roman Empire) suggesting persecution and caution.

-

Resembles a Jewish scribe or teacher living in diaspora, possibly Babylon or Egypt, which had vibrant Jewish communities.

🎯 Why Was It Written?

1. To Wrestle with Theodicy

Why do the wicked prosper while God’s people suffer?

-

A central question in 4 Ezra (chs 3–14).

-

The writer laments Israel’s judgment, trying to understand how a righteous God could allow such horror (especially 3:28–36).

2. To Offer Apocalyptic Hope

God has a hidden plan. The end is coming. The righteous will be vindicated.

-

An angel (Uriel) reveals timelines, signs, and visions of a coming messianic age.

-

Messiah will reign for 400 years (7:28–29), followed by resurrection and judgment, this is debatable knowing that the Messiah will reign forever.

3. To Encourage Endurance During Roman Oppression

-

The symbolic eagle vision (chs 11–12) likely critiques the Flavian emperors (Vespasian, Titus, Domitian).

-

Suggests that although Rome rules now, its fall is certain.

4. To Preserve and Pass On Revelation

-

In chapter 14, Ezra is commanded to write 94 books, but reveal only 24 to the public (matching the Hebrew Bible canon).

-

The other 70 books are secret, for the wise.

-

This echoes traditions of hidden knowledge, possibly linked to the Dead Sea sectarians or early mystical Judaism.

🧩 Summary of What We Know

| Feature | Detail |

|---|---|

| Likely Author | Anonymous Jewish sage/scribe |

| Date | After 70 AD, most likely 90–100 AD |

| Location | Possibly Babylon or Egypt (Jewish diaspora) |

| Motivation | Respond to Temple destruction, preserve hope, interpret suffering |

| Literary Form | Apocalyptic dialogue, visions, symbolic prophecy |

| Target Audience | Faithful but confused Jews after 70 AD—those needing answers and strength to endure |

🗝️ Why the Ezra Pseudonym?

-

Ezra was seen as the ideal scribe, lawgiver, and restorer after the Babylonian exile.

-

Using his name gave the text authority and a pattern: just as Ezra explained the past exile, this "new Ezra" explains the new one under Rome.

-

Common strategy in apocalyptic literature: Enoch, Baruch, Moses, and others have pseudepigraphal books written in their names for similar purposes.

📖 1. Was 2 Esdras Read by Early Christians?

✅ Yes — and with interest and reverence.

Although not part of the Jewish Tanakh, 2 Esdras was widely read in early Christian communities, especially among Gentile believers and in regions outside Palestine.

Here’s the evidence:

📜 2. Inclusion in Latin Bibles

-

In the Latin Vulgate, 2 Esdras is called "Esdrae III & IV", and often appears as an appendix after the canonical books.

-

It was included in many early printed Bibles, including the original 1611 King James Bible, where it appears in the Apocrypha section.

-

Jerome, who translated the Vulgate (~400 AD), acknowledged it was not part of the Jewish canon, but he preserved it anyway for its edifying value.

📌 Conclusion: It was viewed as valuable, but not canonical in the strict Jewish sense.

🧙♂️ 3. Theological Themes Early Christians Embraced

a. Apocalyptic Endurance

-

The book teaches that the righteous will suffer before being vindicated (chs 4–7).

-

This theme mirrors the Book of Revelation and other New Testament eschatology.

-

Early Christians saw this as confirming their expectation of tribulation before the return of Christ.

b. Messianic Hope

-

2 Esdras 7:28–29 mentions "my son the Messiah" who will reign for 400 years before death and final judgment.

-

This idea was striking to Christians who already believed Jesus was the Messiah—though the “400 years” reign doesn’t match Christian doctrine, the concept of an earthly Messianic reign resonated.

c. Heavenly Revelation

-

Uriel, the angel, reveals hidden truths to Ezra—just as angels explain visions to John in Revelation.

-

Christian mystics and theologians were drawn to this heavenly knowledge motif.

📚 4. Manuscript Survival — Christians Preserved It

| Language | Who preserved it | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Latin | Western Church | Longest and best-preserved form; includes all 16 chapters. Still found in Catholic Bibles with the Apocrypha. |

| Syriac | Eastern Christians | Especially used by early Syriac-speaking churches, possibly reflecting connections with the Jewish communities of Mesopotamia. |

| Ethiopic (Ge'ez) | Ethiopian Orthodox Church | Considered canonical to this day. They regard it as an inspired writing of Ezra. |

| Greek | Mostly lost | Possibly existed, but no complete Greek manuscripts survive. |

✝️ 5. Church Fathers’ Use

-

Ambrose, Augustine, and others quoted from it or referred to its themes, especially in discussions about judgment and the afterlife.

-

Though not considered canonical by councils like Laodicea (4th c.) or Carthage, it was often cited alongside canonical books for moral instruction.

🔐 6. Why Did Christians Preserve It?

-

It addressed crisis — post-70 AD, the Jewish loss of the Temple paralleled early Christian persecution.

-

It explained suffering — answering the same theodicy questions early believers faced.

-

It pointed forward — to a coming judgment and the hope of a new world.

-

It carried authority — pseudonymously written in Ezra’s name, echoing prophetic and apocalyptic traditions Christians respected.

🧠 Final Thoughts

2 Esdras (4 Ezra) may not have made it into the formal canon for most Christian groups, but it was:

-

Read devotionally

-

Quoted by Church Fathers

-

Preserved in multiple Christian traditions

-

Canonized by the Ethiopian Church

-

And strongly respected for its spiritual insight

#2Esdras #apocryphaIt served as a bridge between the Hebrew prophets and the Christian apocalypse — standing beside Daniel and Revelation as a voice crying out in times of trial: "Be patient, the end is near, and the righteous will shine like the stars."